What role do Indigenous communities play in climate preservation and restoration?

As climate change progresses, we are more frequently hearing about the impacts on Indigenous people and their communities, but how do we define a person or community as Indigenous? The most widely accepted definition is a community that has a historical association with a region prior to colonization and its people identify themselves as Indigenous.

Indigenous peoples inhabit all regions across the world, representing a rich tapestry of over 4,000 distinct languages and 5,000 unique cultures. However, despite their rich heritage, they comprise just 5% of the global population. Moreover, Indigenous communities continue to endure the harsh realities of ongoing systemic discrimination, which severely restricts their ability to practice their cultural traditions and impacts their physical well-being.

Despite these challenges, Indigenous communities protect 80% of Earth’s biodiversity. They are able to accomplish this through several practices, including community-based conservation, and biodiversity-friendly practices, which are both informed by Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK). Community-based conservation makes each individual within a community responsible for protecting nature, and it leads to better outcomes for ecosystems. Indigenous communities implement biodiversity-friendly practices through rotational farming, selective harvesting, and traditional hunting techniques, which prevent the overexploitation of natural resources. Both of these practices, among others, are largely informed by hundreds of years of knowledge that these communities have accumulated through living in close proximity and harmony with specific environments.

Indigenous communities play a vital role in mitigating the impacts of climate change by using traditional knowledge for sustainable ecosystem management. Their knowledge of traditional food practices, including sustainable farming, fishing, and hunting, allows them to gather natural resources in a way that supports a healthy ecosystem. By rotating the crops that are being farmed and harvested, it keeps soils healthy and full of nutrients, and the lack of pesticides preserves the health of local bodies of water. The combination of these practices allows them to have a balanced ecosystem full of biodiversity.

Some countries have taken steps to honor the rights of their indigenous peoples. Recently, Brazil announced that it’s annulling mining on indigenous lands, increasing the protection of indigenous peoples and creating the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples. These actions will increase the strength of indigenous communities and serve as a step towards repairing 500 years of inequality, as well as combating deforestation in indigenous lands. As other countries begin to follow suit, it’s crucial to demand concrete implementation, not just formal recognition of the community’s struggles and needs. Creating groups such as the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples is certainly a good path to follow, as it acknowledges the need for direct communication and accountability. Our partner, Pachamama, is helping Indigenous communities in the Amazon rainforest obtain rights to their land by providing communities with legal support. It is important for Indigenous communities to own the land that they have spent so long protecting.

“Only when the last tree has died and the last river has been poisoned and the last fish has been caught will we realize that we cannot eat money.”

– Chief Seattle, Suquamish and Duwamish chief

Many different industries threaten the sovereignty of Indigenous Peoples. One such industry is the oil industry. Hydraulic Fracturing, or fracking, as it’s commonly known, is a method used by many different oil producers to obtain oil and natural gas. Fracking uses a method that creates miniature earthquakes while drilling for fossil fuels, and these tremors can create seismic slips or larger earthquakes. This process creates a large amount of wastewater, emits greenhouse gasses, and is a noise disturbance. The increase in noise can cause migratory disruptions, leaving an unbalanced ecosystem behind. Because this process is so intrusive, it has historically been conducted in poor and rural areas, leaving these communities to bear the environmental burdens. Indigenous communities are working to reduce fracking in these areas by creating buffer zones, and their movement has gained serious attention.

To combat the excessive fracking takeover, Indigenous communities have been fighting for Rights of Nature laws, with the Ponca Nation being the first to pass a law in 2017. Fracking has since been banned on their lands. They later passed another law in 2022 acknowledging and protecting the legal rights of two rivers. A more well known case was the Dakota Access Pipeline, which threatened the Sioux reservation primarily, along with others. The long battle began with protests from local tribes and environmental groups, followed by Judge James Boasberg’s ruling in 2020 that federal officials failed to complete a full analysis of the environmental impacts. Unfortunately, the pipeline continued operations in 2021 because the Standing Rock legal team was unable to demonstrate that there would be irreparable injury to nearby areas and people. The U.S. Army Corp of Engineers was forced to do another environmental assessment of the pipeline, which was released on September 8th, 2023. To learn more about what this assessment could mean for the Sioux Tribe, click this link for a 10-minute podcast.

Though many Indigenous communities fight climate change industries and harmful environmental practices, these communities are not immune to the impacts of climate change. In fact, they feel the effects of climate change before most other communities. Climate change does not just impact our environment, it has a socio-economic impact as well. Indigenous communities lose access to their lands through droughts, floods, and wildfires, which disrupt their food sources, infrastructure, political power, and the natural ecosystems upon which many communities have relied for hundreds of years. This leads to a loss of Indigenous identity, which is intimately tied to land, as well as the traditional ecological knowledge that goes with it.

“We are not merely the leaders of tomorrow; rather, we are the leaders of today,” declared Kalikoonāmaukūpuna Kalāhiki, an inspiring advocate for environmental justice and Indigenous sovereignty. With unwavering determination, Kalikoonāmaukūpuna has taken their advocacy from college campuses to the nation’s capital, Washington DC, striving to address pressing land rights issues and the ongoing challenges posed by pipelines. However, Kalikoonāmaukūpuna is not alone in this endeavor. Across Indigenous communities, young activists are stepping up to take charge, asserting their voices, and rallying for meaningful action against climate change. Their involvement in climate activism is both a reflection of their deep-rooted connection to the land and a testament to their resilience in the face of environmental threats. By reaching out to their communities and engaging with policymakers, these Indigenous youth are determined to usher in transformative change, ensuring the protection of their precious ecosystems and the advancement of their vital causes. As allies, we have the privilege and responsibility to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with these young leaders, offering our support and commitment to collectively safeguarding our shared planet for future generations.

Recently, Colleges and Universities in the U.S. have been exploring creative ways to recognize tribal lands, such as flying their official flags on campus or offering free tuition to Native American Students. More national movements, such as the LandBack movements, have also been pushing for reforms and reparations.

It is crucial that organizations and governments alike take the effort to recognize the fact that the land they occupy had previous owners. Please watch this 10 minute video about the LandBack movement and answer these questions below in 200 words or more:

Upload a PDF document with answers to the above questions. Include your name (or team name), username, and school on your upload.

Submission Guidelines

The Dakota Access Pipeline has a longstanding legal history from 2015 to present day. The pipeline has shut down at various times, but various federal courts have managed to prevent a final shutdown as corporations have been able to provide impact statements that minimize the environmental and social impact of this pipeline.

Research a current example of Indigenous land ownership, sovereignty, or other human rights being violated by a government or industry. It could be in your country, or in another country around the world, as long as the example resonates with you. If you need some inspiration, check out Amnesty International’s webpage on Indigenous Peoples or the Human Rights Watch webpage on land rights.

Next, create a powerful call to action that seeks to bring justice for this particular Indigenous group. Tag local or national leaders that might have power over the situation, and reach out to activists already fighting against this violation of Indigenous rights.

In your call to action, be sure to provide the background for the situation, what is being done to address it, and what needs to be done for it to be resolved.

Be sure to tag any accounts associated with the Indigenous peoples you are referencing, as well as @pachamamaorg, @TurningGreen and #PGC2023.

Upload a PDF document with a screenshot of your call to action and a screenshot of your post on Instagram. Include your name (or team name), username, and school on your upload to be eligible to win.

Submission Guidelines

Organizations around the world are working to preserve indigenous land and culture. Our partner, the Pachamama Alliance works to empower Indigenous people of the Amazon rainforest. If Not Us Then Who is building indigenous networks through storytelling. What can we learn from these cultures?

Storytelling is an integral tradition within many Indigenous communities. Choose one Indigenous group that resonates with you or your region and read a story or watch a film (check out the organizations listed above as a place to start) to learn about the history and culture of this particular group. Share your learnings with us by recounting the story and the knowledge that the story imparts.

Post a meaningful artistic rendering of the story through a medium of your choice (drawing, painting, collage, etc.) and include a synopsis of the story that you choose in your caption on Instagram. Tag any accounts associated with the Indigenous peoples you are referencing, as well as @pachamamaorg, @TurningGreen and #PGC2023.

Upload a PDF document with your responses, an image of your original artwork, as well as a screenshot of your Instagram post. Include your name (or team name), username, and school on your upload to be eligible to win.

Submission Guidelines

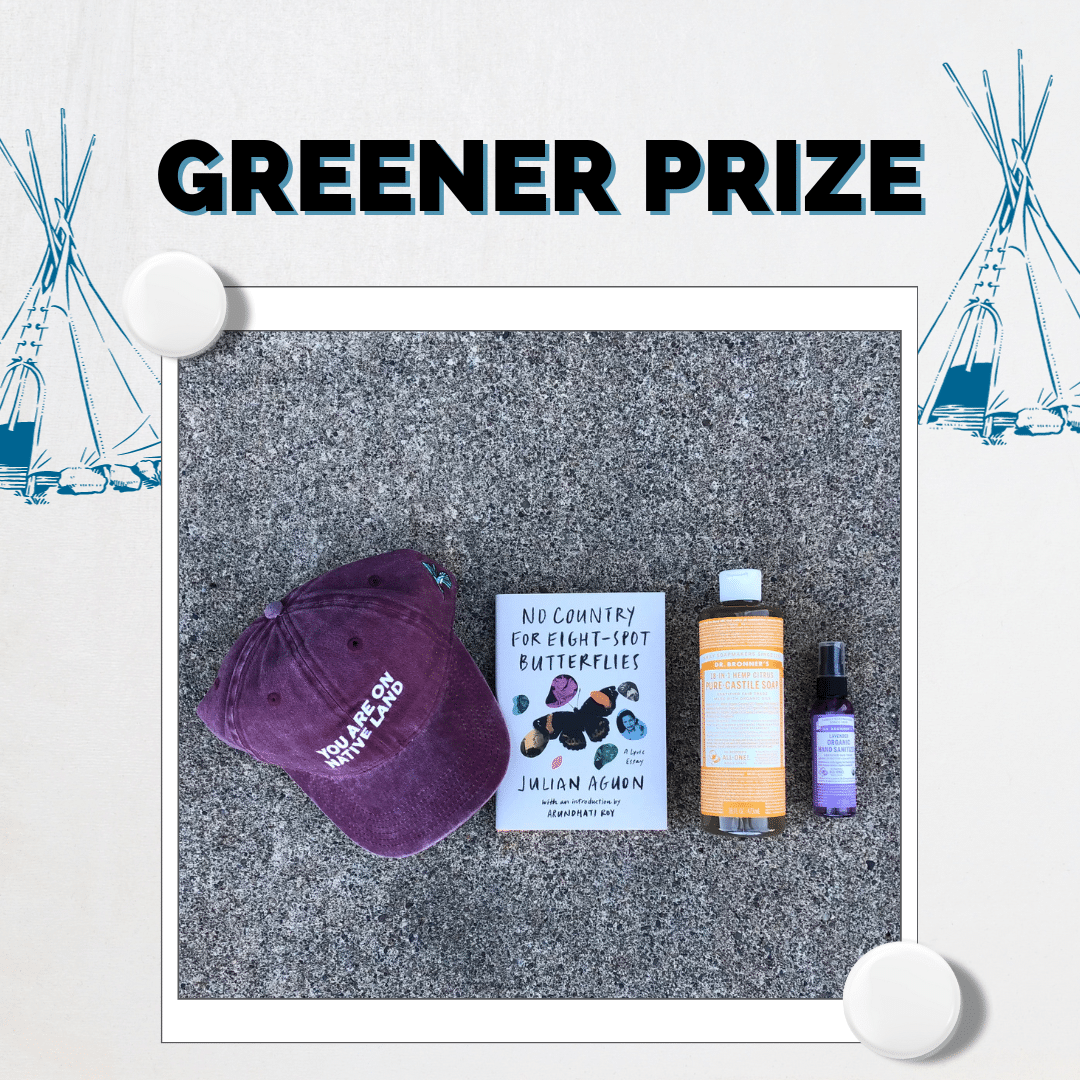

Up to 10 Greener and 10 Greenest outstanding submissions will be selected as winners.